Morris Loeb is a much treasured figurehead to the Chemists' Club and extended chemical community. He had a quick mind and a giving heart, which has provided a plethora of scientific advances as well as charitable contributions to the chemical community at large. The following account of his life has been gleaned from several key publications attesting to the prolific character and work ethic of Morris.

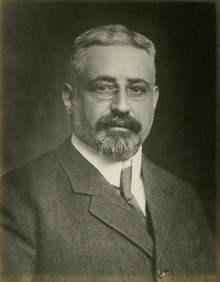

Morris Loeb, President, 1909-1910

"Much has been written about Morris Loeb by those who were close to him, both professionally, academically and personally. I cannot pretend to know him, and as such cannot attest to his nature except by reference. This account of our beloved founder is drawn from a myriad of published work and testimonials, with the goal of presenting the flavor of the life and character of this extraordinary chemist, scholar, philanthropist and human being. I thank Jay Thompson and Chat De Silva for their contributions and healthy discussion." -Gordon Brown, Chemists' Club Student Leader

Prof. Dr. Morris Loeb, May 23rd 1863 - October 8th 1912, was born to Solomon Loeb and Betty (Gallenberg) Loeb in Cincinnati, Ohio. His father had emigrated from Worms, Rhineland-Pfaltz, Germany to Cincinnati in 1840, becoming a prominent dry-goods merchant in Ohio. Betty, the daughter of a professional musician, loved music and learning and instilled these interest in her children through diverse lessons and family musical events.

At the age of two, the Loeb family moved to New York City to take advantage of the economic expansion of the 1860s with his fathers’ brother-in-law and business partner Abraham Kuhn, starting the banking house of Kuhn, Loeb and Co. The enormous success of Kuhn, Loeb and Co. made the company one of the great US investment banking firms of the 19th and 20th century rivaling JP Morgan to fund nationwide railways and the industrial age. Kuhn, Loeb and Co. merged into Lehman Bros in 1977 and Barclay’s in 2008, The banking prominence ensured that Morris and his siblings would enjoy financial rewards of this success.

Morris undertook primary and secondary education at the Sachs Collegiate Institute on the Upper West Side (now the Dwight School). Sachs Collegiate Institute was established by Dr. Julius Sachs, and emphasized classics, language and German discipline. Whilst his brother James would follow in his father’s footsteps into banking (and later establishing the Loeb Classics Library), Morris excelled in science and opted for the pursuit of knowledge. He commenced his university education at sixteen entering Harvard University in 1879, an early reminder of his work ethic and academic prowess.

During his time at Harvard, Morris was deeply influenced by the charismatic Charles Loring Jackson, the hardworking Henry Barker Hill and inspiring Wolcott Gibbs to pursue chemistry. Jackson and Hill were pillars of the german influence on global organic chemistry that helped spread knowledge throughout the United States education community. Loeb ultimately undertook undergraduate research in the lab of the Rumford Professor Wolcott Gibbs, who also studied in Germany, to work on electrolysis. Gibbs studied at Columbia University and taught at City College of New York (f/k/a Free Academy) and founded the Union League of New York City. Morris flourished under Gibbs. .............. He graduated magna cum laude in 1883, and at Gibbs’ recommendation moved to Berlin to commence his Ph.D. with the famed professor August Wilhelm von Hofmann 1. Here he studied the action of phosgene on amidine compounds, and the reactivities of the various derivatives; his research culminated in the publication of his first two scientific papers and his thesis. He received his doctorate in 1887.

Loeb was a devoted and enthusiastic Harvard man, who set himself fully into the activities of the college at this time. His talents as a violist where utilized in the Harvard’s prominent college orchestra, the Pierian Sodality (now the Harvard Radcliffe Orchestra), where he became President. The Pierian Sodality was initially formed by six Harvard men as an organization ‘dedicated to the consumption of brandy and cigars as well as the serenading of young ladies’. His rich cultural upbringing, grâce à his mother Betty, ensured that Morris had a place in most literary societies in college and the best social clubs. Even in his late teens, Loeb was attributed with having thoughtfulness for the welfare and happiness of others partnered with a humility which serve as early reminders of his philanthropic character which we still laud today.

Loeb continued his studies in Germany, firstly with Robert Bunsen in Heidelberg, then at Leipzig with Wilhelm Friedrich Ostwald in what could be considered his postdoctoral research. It was in this ‘hothouse of intellectual curiosity’ that Saltzmann contends Loeb’s transformation into a physical chemist was rendered complete. In collaboration with Walther Nernst, Loeb sought to validate the theory of electrolytic conductivity of Friedrich Kohlrausch by calculating the velocity of the silver ion in solution. The outcome confirmed the independent nature of ions in solution, in that discreet electrolytes have definite and constant amount of electrical resistance as a function of concentration. Testing a panel of silver salts Loeb observed a consistent value for silver across the series, giving satisfactory evidence for Kohlrausch’s theory. Likewise, Loeb proved that the molecular weight of iodine changes as a function of concentration in alcoholic solution by using vapor-tension (osmotic pressure). These findings were key building blocks for the development of ionic theory. It was in 1888 when Loeb returned to the United States to work in the private laboratory of his undergraduate advisor Wolcott Gibbs, who had recently retired from Harvard and had established himself in Newport, Rhode Island.

1) In 1856, Hofmann's student William Henry Perkin was attempting to synthesize quinine at the Royal College of Chemistry in London, when he discovered the first aniline dye, mauveine. The Perkin Medal is an award given annually by the Society of Chemical Industry (American Section) to a scientist residing in America for an "innovation in applied chemistry resulting in outstanding commercial development." It is considered the highest honor given in the US chemical industry. The Perkin Medal was first awarded in 1906 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the discovery of mauveine, the world's first synthetic aniline dye, by Sir William Henry Perkin, an English chemist. The award was given to Sir William on the occasion of his visit to the United States in the year before he died. It was next given in 1908 and has been given every year since then.

Over the course of Loeb’s year in Rhode Island, Gibbs realized Loeb’s mastery as a teacher and advocated to secure him a position as a docent in physical chemistry at the newly established Clark University. It was at Clark University where Loeb made several notable contributions to the chemistry community; he taught what could be considered the first physical chemistry course in the United States; was one of 43 chemists who attended the first American Chemical Society national meeting which has held outside New York; and espoused the use of the Gooch Crucible as an instrument for the exact measurements of electric currents. As a result of his efforts, Loeb was appointed Professor of Chemistry at New York University in 1891, becoming the first physical chemist to be a full professor in a chemistry department in the United States.

It was at New York University where a new chapter in the life of Morris Loeb was forged. Under the additional responsibilities of teaching and administration, which he thoroughly enjoyed, the time he devoted to research was appreciably diminished. Nonetheless, he pursued his passion for research. Four years later, Morris was appointed the chair of chemistry at New York University. He held this position for eleven years. At the age of 75, Solomon Morris passed, and being the eldest in his family, Morris assumed much of the responsibilities of his father in the civil, religious and charitable work associated with the Loeb family. A few years later, in 1906, he resigned from his post New York University. Weighing his filial duty, professorial obligations and his research aspirations, it was clear to Loeb that certain sacrifice would be required of him. Friend to Loeb, Charles Baskerville comments that ‘he said he would have to give up the professorship, but would equip a private laboratory in the old Chemists’ Club, a professional club Morris had founded in 1898, where we would be nearer to his philanthropic obligations and might do some research, and other things perhaps as useful to chemistry as teaching.

Whilst his formal calling as a professor drew to a close in 1906, Morris would remain an educator and researcher through his work at The Chemists’ Club and his philanthropic endeavors. Before the club was founded in 1898, members of the American Chemical Society and the Society of Chemical Industry held events and meetings in homes, classrooms, and lecture halls, using whatever space was available. Accommodations in New York City were not sufficient for these educational and commercial events which led to Morris Loeb founding The Chemists’ Club in 1898.

As president of The Chemists’ Club, Loeb saw the need for a central organizational hall for chemists as well as a world-class chemical laboratory and helped establish a permanent home for the nascent organization through his provision of a building at 50 E 41st St in New York in 1910. Loeb personally oversaw every detail of its construction. Succeeding through his will and ideology, The Chemists’ Club emerged as the premier networking hub where academic and industrial minds come together to provide solutions for modern challenges. Having resigned from New York University, Loeb fully furnished a chemical laboratory in the loft of the Chemists’ Club which could be rented by members. In addition, Loeb established a world-class chemical library, portions of which were later donated to the Chemists' Club Othmer library of the Chemical Heritage Foundation in Philadelphia for safekeeping and preservation.

Through The Chemists’ Club, Morris would remain connected with the New York Academy of Sciences, the American Chemical Society, the Deutsche Chemische Gesellschaft, the American Electro-Chemical Society, the New York Electric Society and the Society of Chemical Industry until his death.

The Loeb name is synonymous with personal excellence and professional development within the circles associated with Morris. His love of the arts and science, and passion for community led him to establish club buildings which would serve as continual meeting places for practitioners of their craft; He served as a major donor for the Wolcott Gibbs Laboratory, aiding in the development of chemistry at Harvard. Furthermore he raised considerable funds for the procurement of a building to situate the Chemists‘ Club in Manhattan.

Loeb believed in preventative philanthropy rather than in remedial charity and as such was associated with a great number of charities; He was President of the Hebrew Technical Institute for Boys, President of the Solomon and Betty Loeb Memorial Home, Director of the Jewish Agricultural and Industrial Aid Society, Baron de Hirsch Fund, a trustee of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America and a founder of the American Jewish Committee, amongst many private endowments he bestowed to individuals.

His far reaching interest in helping those he could is best shown through his numerous bequeathments upon his passing; notably the establishment of the Loeb Lectureship at Harvard which continues to this day, the establishment of a chemical museum at the Chemists‘ Club and the division of his wealth amongst notable New York institutions, including the American Museum of Natural History, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Cooper Union, the Hebrew Technical Institute, the New York Foundation, the Jewish Protectory and Aid Society, the Hebrew Charities Building and the Educational Alliance.

Another lasting mark of Loeb‘s commitment to higher education is at Harvard where the Morris Loeb Lectureship was established in 1953 by the Department of Physics under the terms of the bequest of Morris Loeb, A.B., 1883.

Even to this day, Morris‘ legacy can be seen in the prestigious events The Chemists‘ Club hosts each year:

The Kavaler Award in honor of the top CEO in the chemical industry as recognized by their peers

Winthrop Sears Medal for outstanding innovative and entrepreneurial achievement at the National Academy of Sciences

Annual Egg Nog Gala celebration promoting good will and charity with the university community

"The Electrolytic Dissociation—Hypothesis of Svante Arrhenius," American Chemical Journal, Vol. 12, pg. 506-516

"The Use of the Gooch Crucible as a Silver Voltameter," Journal of the American Chemical Society, Vol. 12, pg. 300

"Ueber die Einwirkung von Phosgen auf Aethenyldiphenyldiamin," Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft, Vol. 18, p 2427

The Conditions Affecting Chemistry in New York, Morris Loeb, Science, 1909, vol 30, pg. 664

Morris Loeb: Ostwald‘s first American student and America‘s first physical chemist, Martin Saltzmann, Bull. Hist. Chem. 1998 22, 10

Morris Loeb 1863-1912, Chemists‘ Club, New York

Morris Loeb, Cyrus Sulzberger, Am. Jew. Hist. Soc., 1914, 22, 225-227

The Professional Work of Professor Morris Loeb, Charles Baskerville, Science, 1912, 664-667

The Scientific Work of Morris Loeb, Theodore William Richards